Introduction

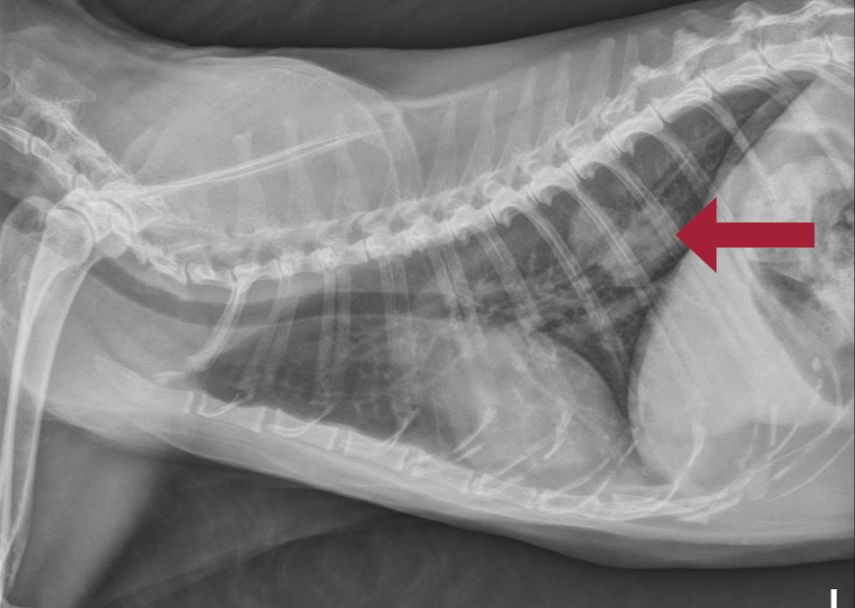

X-rays have long been used by veterinarians as a diagnostic imaging tool to detect tumors and cancer in dogs. An x-ray creates images of the inside of a dog’s body using small doses of radiation. Since tumors and cancerous tissues often have different densities than normal tissue, x-rays can reveal abnormal masses or growths that may indicate cancer.

While x-rays are useful for tumor detection, they have limitations. Not all tumors will show up on x-rays, and some cancers are difficult to identify using this method alone. However, x-rays remain one of the first steps a veterinarian will take when cancer is suspected in a dog. When combined with other diagnostic tests, x-rays can play an important role in early cancer detection and determining proper treatment.

How X-Rays Work

X-rays produce images using invisible electromagnetic radiation. When the radiation passes through the body, it is absorbed in different amounts depending on the density of the material it travels through. Denser materials like bone absorb more x-rays than soft tissues, causing differences in the amount of radiation that reaches the x-ray detector. These differences are used to produce images of structures inside the body. The radiation is produced by accelerating electrons at high speeds in an x-ray tube to hit a metal target. The collisions with the target produce x-ray photons that radiate in all directions. The useful x-rays are directed toward the patient in a narrow beam.

According to https://www.independentimaging.com/x-rays-work/, X-rays involve radiation that passes through the body but you can’t feel it or see it. The different densities of body structures absorb the radiation differently, allowing an image to be produced based on the radiation that exits the body and hits the detector.

Types of X-Rays

There are several different types of x-rays that can be used to examine dogs for potential tumors:

Plain films are basic x-rays that provide an overview of bone and some soft tissue structures. They allow veterinarians to see things like tumors, fractures, and foreign objects (according to https://southwestxray.com/types-of-animal-xrays/).

Contrast studies involve giving the dog a contrast agent by mouth or injection to enhance the visibility of structures like the digestive tract. This can help identify masses or blockages (according to https://www.merckvetmanual.com/clinical-pathology-and-procedures/diagnostic-imaging/radiography-of-animals).

CT (computed tomography) scans use x-rays and computer processing to create cross-sectional images of the body. This allows for detailed views of soft tissues and can be useful for locating tumors (according to https://www.vetmed.ucdavis.edu/hospital/diagnostic-imaging/small-animal/xray).

MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) uses magnetic fields and radio waves to produce detailed images of organs and tumors without radiation. However, it often requires anesthesia and is more expensive.

Using X-Rays to Detect Tumors

One of the primary uses of x-rays in dogs is to detect tumors and cancers. According to a blog post by Mountainaire Animal Clinic, “X-ray images can help vets spot some tumors” (source). X-rays work by passing radiation through the dog’s body and capturing the resulting image on film. Denser materials like bone show up as lighter areas, while softer tissues appear darker.

When looking for tumors, the veterinarian will examine the x-ray for any abnormal masses or growths. These may appear as irregularly shaped light or dark areas depending on the density of the tumor compared to surrounding tissues. According to Dog Cancer Blog, vets also look for “bone destruction” that can indicate cancer has spread to the bones (source). Areas where the bone appears “eaten away” or mottled can signify bone cancer.

However, while x-rays can detect some tumors, they have limitations in finding cancers like lymphoma that may not have a well-defined mass. Other diagnostic tests like CT scans, ultrasounds, or biopsies may be needed to fully diagnose or stage cancers.

Limitations of X-Rays

While X-rays are a common and useful diagnostic imaging tool, they do have some limitations when it comes to detecting tumors in dogs. One key limitation is that X-rays are not always definitive in determining if a mass or lesion is cancerous (source). Since X-rays provide 2D images of 3D structures within the body, they may not clearly differentiate a tumor from normal surrounding tissues. Additionally, some tumors have densities or compositions that are very similar to healthy tissues, making them nearly impossible to visualize on X-rays (source). Soft tissue tumors in particular, like those arising in the abdomen or chest, can be extremely challenging to diagnose with X-rays alone.

Even bone tumors, which should theoretically show up well on X-rays due to the density differences between tumor and normal bone, are not always clearly visualized. Aggressive bone tumors can cause bone destruction that appears similar to non-cancerous orthopedic diseases on X-rays. Benign bone tumors may also be difficult to differentiate from normal anatomical variations in bone shape or structure (source). Overall, while X-rays can provide clues, they often cannot provide a definitive diagnosis of cancer without biopsy or advanced imaging.

Other Diagnostic Tests

While x-rays can be useful for detecting some tumors, they have limitations in identifying cancer in dogs. There are other tests veterinarians may use to diagnose canine cancers:

Biopsy

A biopsy involves taking a small sample of tissue from the tumor and examining it under a microscope. This allows the veterinarian to determine if the cells are cancerous and identify the type of cancer. Biopsies provide the most definitive diagnosis but do require a minimally invasive procedure.

CT Scan

A CT or CAT scan uses x-rays and computer technology to create cross-sectional images of the body. It can detect tumors in soft tissues that may not show up on regular x-rays. CT scans involve anesthesia and radiation exposure.

MRI

An MRI uses magnets and radio waves to generate detailed 3D images of organs and tissues. It excels at imaging soft tissue cancers. However, MRIs require anesthesia and are more expensive.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound uses high-frequency sound waves to create images of internal structures. It can identify and characterize masses and tumors. Ultrasound is non-invasive but limited in assessing some areas of the body.

While more advanced than x-rays, these imaging tests also have limitations in cancer detection. Often multiple tests are needed to fully diagnose canine cancers.

Benefits of Early Detection

Detecting tumors early on in dogs can greatly improve their prognosis and provide more treatment options. The earlier a tumor is found, the better the chances are of successfully removing it or slowing down its growth. Some of the key benefits of early detection include:

Better Prognosis – Dogs whose tumors are caught early when they are small and localized have a much better prognosis. Treatment is more likely to be effective before the cancer spreads to other parts of the body. The survival times for dogs after early treatment can often be measured in years instead of months.

More Treatment Options – In the early stages of cancer, surgery may be able to completely remove a tumor. Radiation and chemotherapy are also more effective when the cancer is localized. Advanced tumors that have metastasized may be impossible to completely remove and are more resistant to treatment.

The Most Common Canine Tumors

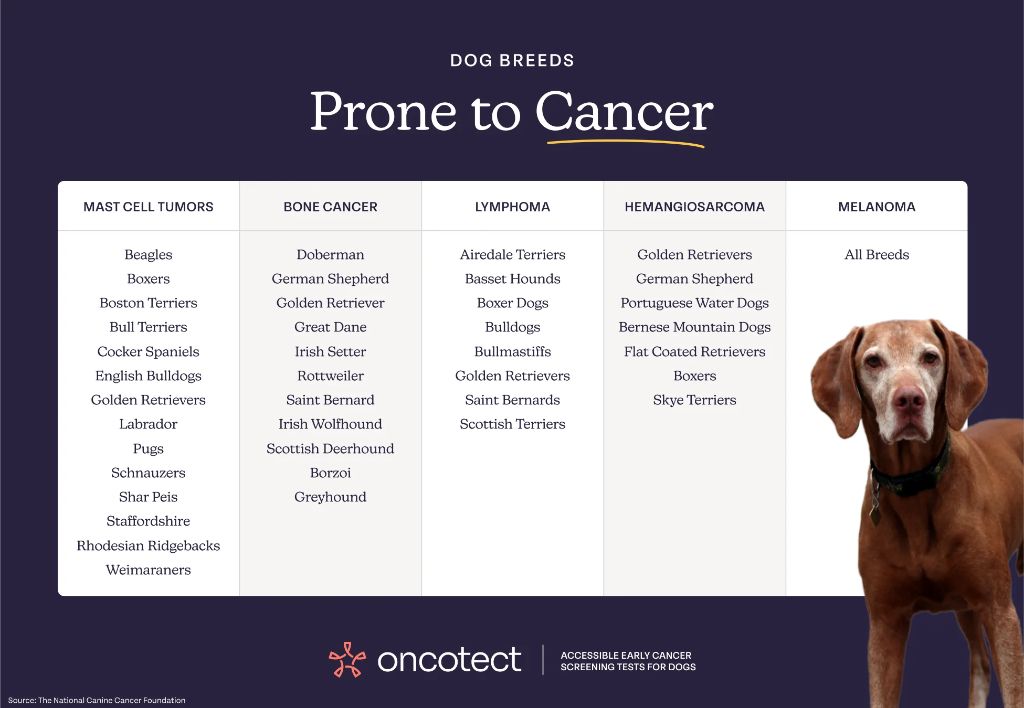

According to data from the Swiss Canine Cancer Registry, the most commonly diagnosed malignant tumors in dogs are:

- Mast Cell Tumors – Mast cell tumors are the most frequently diagnosed skin tumor in dogs, accounting for up to 20% of all skin tumors. They originate from mast cells located in the skin, respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal tract. Mast cell tumors in dogs often appear raised andFirm, and range in size from a pea to several inches across.

- Lymphoma – Lymphoma is one of the most common cancers seen in dogs. It develops from lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell, and causes solid tumors to form in the dog’s lymph nodes and other organs. Dogs of any age are susceptible, but it occurs mostly in middle-aged to older dogs (6 years and older).

- Osteosarcoma – Osteosarcoma (OSA) accounts for approximately 85% of all bone tumors seen in dogs. It is an aggressive cancer that affects large and giant breeds, especially Great Danes and Irish Wolfhounds. OSA often strikes the dog’s legs, causing lameness, swelling, and bone pain.

Early detection and treatment is critical for these common dog cancers. Regular veterinary checkups and immediate attention to any suspicious lumps or swellings can help improve outcomes.

Treatment Options

The three main treatment options for canine tumors are surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy.

Surgery is often the first line of treatment and can involve removing the tumor itself or the affected area/organ depending on the type, size, and location of the tumor. Surgery aims to fully remove the cancerous tissue with clean margins. However, some tumors cannot be fully removed due to their size or location.

Chemotherapy uses anti-cancer drugs to kill cancer cells and shrink tumors. It may be used before surgery to make the tumor smaller and easier to remove. Or it may be used after surgery to kill any remaining cancer cells. Chemotherapy can have significant side effects in dogs, so vets carefully determine dosage and treatment schedules.

Radiation therapy uses high energy beams to kill cancer cells and shrink tumors. It may be used alone or with surgery and/or chemotherapy. Radiation is focused on the tumor area to avoid damage to healthy tissue. Side effects can include skin irritation and fatigue. Treatment schedules vary based on the type of radiation used.

Vets will recommend the most effective treatment plan for an individual dog based on the type, size, grade, and stage of the tumor as well as the dog’s overall health.

Sources:

http://jwee.blog.fc2.com/blog-entry-3.html?sp

Prognosis

The prognosis for a dog diagnosed with cancer depends significantly on the type, grade, and staging of the tumor. Just as in human medicine, cancers caught earlier when localized (before spreading to other areas of the body) have a better prognosis. According to the American Veterinary Medical Association (AMVA), approximately 50% of dogs over the age of 10 will develop cancer. However, the median survival time for dogs after a cancer diagnosis ranges widely – from weeks or months for very aggressive cancers that have already metastasized, to years for small, low-grade tumors caught early.

For example, according to the Great Pet Care, one of the most common cancers in dogs is lymphoma, which has a median survival time of 12-14 months with treatment but only 1-2 months without. On the other hand, dogs diagnosed early with a small mast cell tumor localized to the skin have upwards of a 95% prognosis if the tumor is surgically removed. Other factors that influence prognosis include the dog’s overall health and response to treatment.

Having a veterinary oncologist stage the cancer and grade the tumor cells after diagnosis gives vital information to determine the prognosis and best course of treatment. Working closely with your veterinarian and following their recommended treatment plan provides dogs diagnosed with cancer the best odds of remission and a positive prognosis.