Introduction

Genetic knee problems are relatively common in dogs, especially in certain breeds like Labrador Retrievers, German Shepherds, and small toy breeds. These conditions, which affect the stifle joint, include osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), luxating patella, and cranial cruciate ligament disease. While the specific genetic and environmental factors are still being researched, there is evidence that genetics play a significant role in the development of these conditions.

Understanding the genetic component is important, as it can help breeders screen and select away from affected dogs. It also allows owners to better monitor high-risk dogs for early signs of disease. With some conditions like luxating patellas, early intervention can greatly improve outcomes. Being aware of breed risks empowers owners to provide the best care through prevention, early diagnosis, and appropriate treatment.

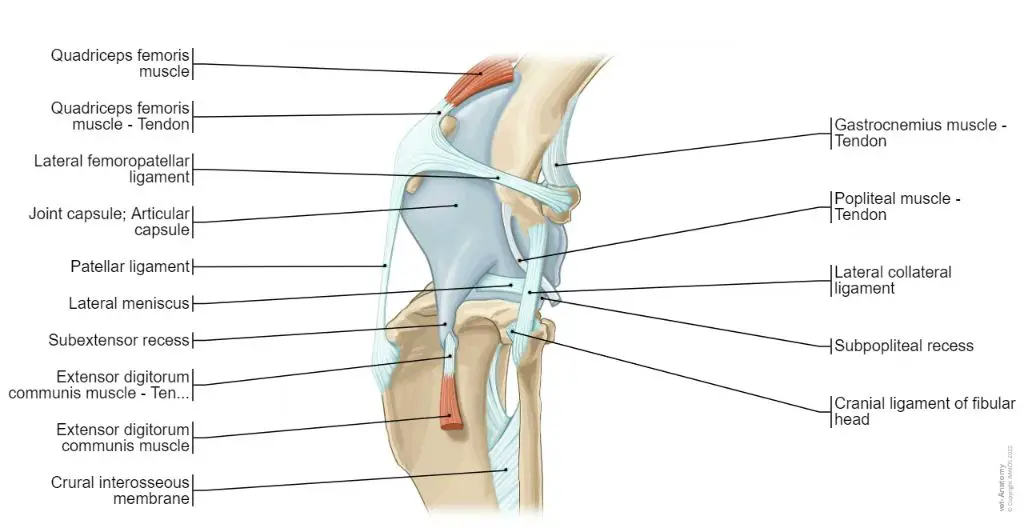

Anatomy of a Dog’s Knee

A dog’s knee joint is complex and allows for flexion, extension, and rotational movement of the hind leg. It consists of the femur (thigh bone), tibia (shin bone), and patella (kneecap), which all come together to form the stifle joint. The joint is stabilized by ligaments such as the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments, collateral ligaments, and the patellar ligament (TPLO Austin, 2022)

The main ligaments that provide support and prevent excessive motion of the knee joint are the cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) and the caudal cruciate ligament (CaCL). The CCL prevents forward sliding of the tibia in relation to the femur, while the CaCL limits hyperextension. Cartilage called the medial and lateral menisci act as shock absorbers between the femur and tibia (Orthopets, 2022).

Proper functioning of all the ligaments, tendons, cartilage and bones that make up the canine knee joint is essential for normal hind limb mobility and use.

Common Genetic Knee Problems

There are three common genetic knee problems that affect dogs: osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), luxating patella, and cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) disease. OCD and luxating patella tend to affect larger breeds while CCL disease is more common in smaller breeds.

OCD is characterized by loose cartilage within a joint. According to Pet Place, OCD most commonly affects the shoulders, hocks, and stifles in dogs. It occurs when areas of cartilage become thickened and start to separate from the underlying bone. This can lead to joint inflammation and lameness if left untreated.

Luxating patella refers to a kneecap (patella) that moves out of place or luxates. As described by VSEC, this occurs when the groove the patella sits in is too shallow, allowing the kneecap to slide out of place. Smaller dog breeds are more prone to this condition. It causes pain and limping.

CCL disease is the rupture or tearing of the cranial cruciate ligament, one of the major stabilizing ligaments of the knee joint. According to OrthoDog, this condition is seen most often in older, large breed dogs. The torn ligament leads to joint instability and degenerative arthritis over time.

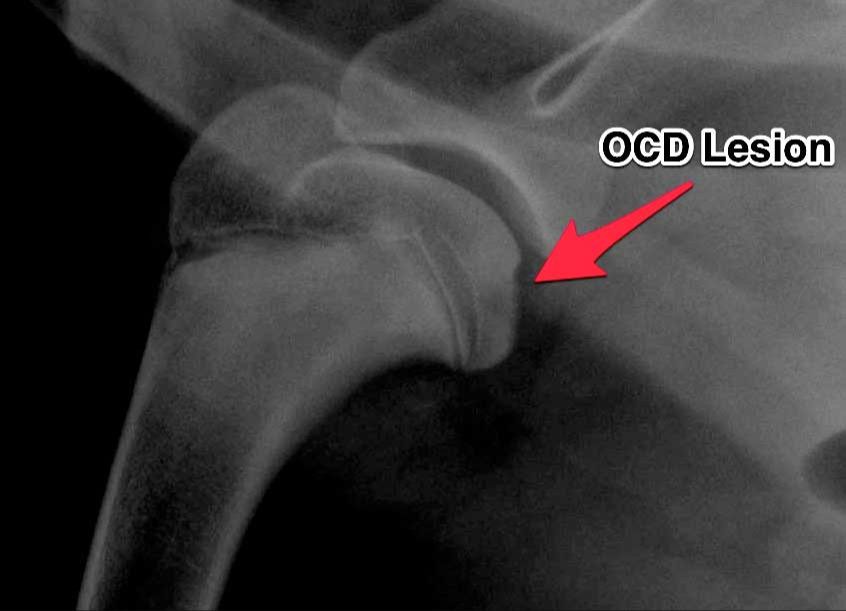

Osteochondritis Dissecans (OCD)

Osteochondritis Dissecans (OCD) is a joint condition that affects the cartilage in dogs, often resulting in lameness. It occurs when a piece of cartilage, along with a thin layer of bone beneath it, begins to separate from the end of a bone at a joint surface.

OCD most commonly affects large and giant breed dogs between 4-10 months of age. However, it can occur in dogs of any size or age. The joints most susceptible to OCD include the shoulder, elbow, knee, and hock.

Common symptoms of OCD include lameness or stiffness in one or more joints, pain, swelling, and decreased range of motion. Lameness tends to worsen after exercise. OCD is often diagnosed through x-rays, though advanced imaging such as CT or MRI scans may be needed to fully visualize the separated cartilage flap.

Treatment depends on the joint affected and severity. Nonsurgical options include rest, restricting activity, pain medication, joint supplements, and adequan injections. Surgery may be needed to remove the flap or stimulate healing through microfracture techniques. Weight management through diet and exercise is also important.

Early diagnosis and treatment is key to slowing the progression of OCD and improving outcomes. Though not curable, dogs can go on to live active lives with proper management.

Luxating Patella

Luxating patella refers to when the kneecap (patella) moves or pops out of place, sliding out of the groove in the femur bone where it normally sits. This condition is also known as a floating kneecap or a slipped kneecap. Luxating patella is common in small and miniature dog breeds such as Chihuahuas, Pomeranians, Yorkshire Terriers, and Poodles.

Luxating patella is graded on a scale from 1 to 4 based on severity:

- Grade 1 – The kneecap can be moved in and out of place but pops back into place on its own.

- Grade 2 – The kneecap can move in and out of place but tends to remain luxated until manipulated back into position.

- Grade 3 – The kneecap sits outside the groove most of the time but can sometimes be manipulated back into place.

- Grade 4 – The kneecap is permanently luxated and cannot be manipulated back into position.

Diagnosis of luxating patella involves a physical exam assessing the stability of the kneecap, palpation of the joint, and grading the severity. X-rays may also be taken. Bilateral luxating patellas (both knees affected) is common.

Treatment depends on the grade of luxating patella but often involves surgery to deepen the femoral groove so the kneecap stays in place. Physical therapy is utilized after surgery. For mild cases, pain medication and joint supplements may help manage the condition.

Sources:

https://www.vetdojo.com/blog/luxating-patella-dogs/

https://rehabvet.com/conditions/luxating-patella-dogs-canine-kneecap/

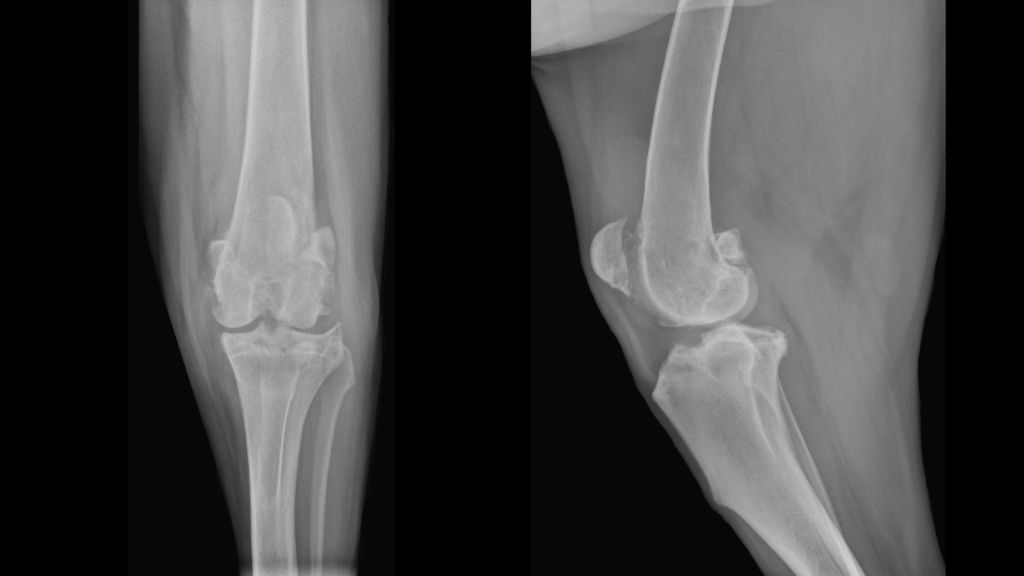

Cranial Cruciate Ligament (CCL) Disease

Cranial cruciate ligament (CCL) disease is one of the most common causes of hind leg lameness in dogs. The CCL is a ligament that connects the thigh bone to the shin bone inside the knee joint and provides stability. CCL disease occurs when this ligament deteriorates or tears, causing pain and instability in the knee joint.

Symptoms of CCL disease include limping or holding the hind leg up, difficulty standing up or reluctance to jump or go up stairs. The knee joint may feel thickened or swollen and “click” when moving. These symptoms start gradually and worsen over time without treatment.

CCL disease is diagnosed by a veterinarian through a physical exam and imaging such as X-rays or an MRI. Imaging can confirm the tearing or rupture of the CCL and also check for other joint issues like arthritis.

Treatment options include surgical repair, knee braces, anti-inflammatory medication, joint supplements, rest, and physical therapy. The most common surgical procedures are tibial plateau leveling osteotomy (TPLO) or tibial tuberosity advancement (TTA) which stabilize the knee joint by altering bone angles and taking tension off the CCL.1

Diagnosing Genetic Knee Problems

A veterinarian will perform a thorough physical exam to check for signs of genetic knee problems in dogs. This includes palpating the joints for evidence of swelling, pain, or instability. The veterinarian will manipulate the knee joint through its full range of motion and may also perform specific orthopedic tests such as the sit test, knee compression test, and tibial thrust test to check for luxating patellas or cranial cruciate ligament injuries.

Diagnostic imaging such as X-rays, CT scans, or MRI can provide important information about the knee joint. X-rays are useful for detecting bone changes associated with OCD and determining the severity of cruciate ligament damage. Advanced imaging like CT or MRI gives a more detailed view of soft tissue structures like ligaments and cartilage.

Arthroscopy or joint endoscopy may also be performed. This minimally invasive procedure involves inserting a tiny camera into the knee joint to directly visualize the cartilage surfaces, cruciate ligaments, and menisci for injury. Samples of joint fluid or tissue biopsies can also be taken during arthroscopy.

Treatment Options

There are several options for treating genetic knee problems in dogs, depending on the severity of the condition. Treatment usually focuses on relieving pain, improving joint mobility, and preventing further damage to the knee.

Nonsurgical Options

For mild to moderate cases, veterinarians may recommend nonsurgical options first. These can include:

- Joint supplements – Supplements like glucosamine, chondroitin, and omega-3 fatty acids can help reduce inflammation and improve joint health.

- Anti-inflammatory medication – Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like carprofen or meloxicam can relieve pain and swelling.

- Weight management – Keeping your dog at a healthy weight reduces stress on the knees.

- Low-impact exercise – Gentle walks, swimming, or physical therapy exercises can maintain muscle tone and range of motion.

- Cold laser therapy – Low-level laser light applied to the knees reduces inflammation and encourages healing.

Surgical Procedures

If nonsurgical options are ineffective, one of the following surgeries may be recommended:

- Tibial plateau leveling osteotomy (TPLO) – reshapes the tibia to stabilize the knee joint.

- Tibial tuberosity advancement (TTA) – moves the tibial tuberosity forward to reduce patellar luxation.

- Lateral imbrication – tightens the lateral collateral ligaments to improve knee stability.

Surgical recovery often includes several weeks of restricted activity followed by physical therapy.

Physical Therapy

Canine physical therapy is an important part of post-surgical recovery as well as management for long-term knee problems. Typical exercises focus on:

- Range of motion – Gentle bending, extending, and rotating of the knee joint.

- Flexibility – Stretches to maintain muscle length around the knee.

- Strengthening – Targeted exercises to improve muscle tone in the hips and thighs.

- Balance – Activities like walking over uneven surfaces, balance boards, or rolling therapy balls.

Lifestyle Modifications

Making adjustments to your dog’s daily routine can also help manage knee problems:

- Ideal body weight – Extra weight stresses joint cartilage and ligaments.

- Comfortable bedding – Cushioned beds reduce pressure on bones and joints.

- Ramps/steps – Avoid jumping on/off furniture by providing stairs or ramps.

- Activity monitoring – Gradually increase low-impact exercise while avoiding high-intensity activities.

Prevention

While genetic knee problems like luxating patella often can’t be completely prevented, there are some steps dog owners can take to reduce the risk and severity of these conditions.

Selective breeding is one approach. Reputable breeders should screen their dogs for genetic diseases and avoid breeding dogs that carry genes linked to knee problems. Mixing breeds that are prone to knee issues can also help dilute the genetic risk. However, this is not foolproof, as some mixed breeds may still inherit problematic genes.

Maintaining an ideal body weight is also important. Excess weight puts more strain on the knee joints, which can exacerbate conditions like luxating patella and osteoarthritis. Following veterinarian recommendations for diet and exercise can help keep a dog trim and healthy.

Joint supplements containing glucosamine, chondroitin, and omega-3 fatty acids may also be beneficial. These compounds help rebuild cartilage, lubricate joints, and reduce inflammation. Talk to your vet about an appropriate supplement regimen for your dog’s age and condition. Supplements will not cure genetic knee problems but may slow their progression.

While genetics play a key role, thoughtful care and preventative measures can still make a big difference in mitigating problematic knee issues for susceptible dog breeds.

Outlook and Prognosis

With early diagnosis and proper treatment, most dogs with genetic knee problems can live a normal life. However, the prognosis depends on the severity and progression of the condition before treatment begins.

For mild to moderate luxating patella, the prognosis is good if treated early before arthritis develops. According to VCA Hospitals, if surgery is performed before arthritis or further injury, the prognosis is excellent and the dog should regain full use of the leg. With proper post-op care, most dogs have a complete recovery.

For OCD, the prognosis is good if caught early before significant cartilage damage. With surgical treatment, OCD generally carries a favorable prognosis. According to the AKC Canine Health Foundation, 75-85% of dogs have acceptable limb function after OCD surgery.

For CCL disease, prognosis is variable and depends on the severity. With early diagnosis and prompt surgical treatment, the prognosis is good. According to VCA Hospitals, over 90% of dogs return to normal or almost normal function after CCL surgery. However, the risk of CCL rupture in the other knee is high.

Ongoing management for genetic knee problems includes keeping your dog at an ideal weight, regular low-impact exercise, joint supplements, anti-inflammatory medication, and physical therapy. With dedicated care, most dogs can enjoy many good years of life.